Chemical warfare enters in October 1914. Sneezing powder. The Germans used 3,000 shells containing the Niespulver, mixed with shrapnel and sent over to the British and Indian troops at Neuve Chapelle. Although not highly effective (the British were not even aware of it being used) this early attempt was aimed at causing discomfort and irritation. Tear gas had even been used by the French in small quantities as early as August 1914.

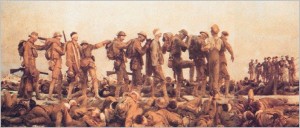

It was an inauspicious start to the campaign of chemical terror and no wonder April 1915 during the Second Battle of Ypres, is the preferred date of its introduction. Chlorine was to prove a greater success than the Germans themselves would realise and they failed to take advantage of the reverses the French and British made upon its arrival. The British themselves at the Second Battle of Ypres were pre warned of the imminent attack as an earlier break through into some German trenches found gas cylinders to be lying about abandoned. Due to some of the previous low impact of earlier strikes, the British were expecting to be able to fan it away without realising this was an entirely new chemical. Reports amounted to some 5,000 casualties on the Allied side.

During the course of the war approximately 3,000 chemicals were to be tried in the

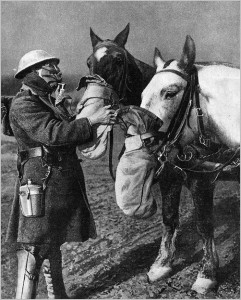

It was not only the soldiers who needed gas masks. From Great War Photos

development of this type of warfare and the Hague’s ban was therefore largely ignored. More was to follow; in the May of 1915 the Russians were to receive an even greater attack by the Germans in which 6,000 Russians were to be killed by the mass attack and again later when a further 25,000 casualties were to suffer. In the October on that year, the Germans were to send over 550 tons of chlorine at Rheims. During the Battle of Loos the British were to retaliate with a bombardment of 150 tons of chlorine, but like the Germans at Ypres, failed to capitalise by adequately supporting the attack. Two lessons had been learned by both sides; the wind change could reverse an attack and also a coordinated gas and subsequent infantry attack could be very successful.

During 1916, chemicals became more effective as Phosgene Chlorine was introduced and 18 times more potent than its predecessor. This was then followed by Diphosgene, which was more effective on the lungs creating a choking effect, had a tear gas element and was more persistent in the trenches. Then in 1917, the Germans, who led in this particular field all through the war, introduced a new idea, mustard gas. Why was it called ‘King of the Gases’? It was more vicious certainly, but it’s true talent was ubiquitous nature. Within six weeks of its introduction in Ypres July 1917, it took 20,000 casualties. By being absorbed in the skin, it could create internal blistering although it was more famous for its temporary or permanent blinding effects. By lying on clothing and foot ware it could be walked into dugouts and trigger its effects on the unsuspecting inhabitants. Areas, which had been hard won, could not be occupied as the gas was left as booby traps. Mustard Gas was a new weapon of terror amongst the rank and file. There was another ill effect it had on morale. As mustard gas had a tendency to attack the sweatier parts of the body, the Scots regiments were eventually discouraged from the use of the kilt.

Although not thought to be an immediate killer (around 6,000 British were killed by its effects, less than 1% of fatalities) the gas is believed to have been a major killer over the years after hostilities ended in 1918. There are powerful arguments which state that to maim was more effective in the art of warfare, as it resulted in a greater consumption of resources than death itself.

DULCE ET DECORUM EST

Bent double, like old beggars under sacks,

Knock-kneed, coughing like hags, we cursed through sludge,

Till on the haunting flares we turned our backs

And towards our distant rest began to trudge.

Men marched asleep. Many had lost their boots

But limped on, blood-shod. All went lame; all blind;

Drunk with fatigue; deaf even to the hoots

Of tired, outstripped Five-Nines that dropped behind.

Gas! Gas! Quick, boys! – An ecstasy of fumbling,

Fitting the clumsy helmets just in time;

But someone still was yelling out and stumbling,

And flound’ring like a man in fire or lime . . .

Dim, through the misty panes and thick green light,

As under a green sea, I saw him drowning.

In all my dreams, before my helpless sight,

He plunges at me, guttering, choking, drowning.

If in some smothering dreams you too could pace

Behind the wagon that we flung him in,

And watch the white eyes writhing in his face,

His hanging face, like a devil’s sick of sin;

If you could hear, at every jolt, the blood

Come gargling from the froth-corrupted lungs,

Obscene as cancer, bitter as the cud

Of vile, incurable sores on innocent tongues,

My friend, you would not tell with such high zest

To children ardent for some desperate glory,

The old Lie; Dulce et Decorum est

Pro patria mori.