BBC coverage of Remembrance Day 2012. Photo of the Cenotaph in Whitehall, London.

This year’s Remembrance Day will have a special significance as it is the centenary year of the start of the Great War. Wokingham Remembers will be discussing the changing attitudes to remembrance on BBC Radio Berkshire, on the 3rd November 2014 at 2pm. We will also attend a special remembrance programme at St Paul’s Church (9th November at 9.30am) which will hear the first rendition of the composer Anna Matthews choral piece ‘From Flanders’, which will commemorate the loss of her ancestors during the Great War. Her Uncles were also parishioners of S Paul’s. This article now tells the incredible story of how Remembrance Day was first conceived.

We stand for the two minute’s silence at 11 am on every November 11th. In the first of those two minutes we try to contemplate those who fought and fell during all wars in all circumstances. The second minute is spent thinking about the lives of those the fallen have left behind.

It is an enormous undertaking and to help me focus on the task, I try to think of my 22 year old Uncle Basil who died in the second war and then his mother who lost both of her sons. Just placing myself in her house in Norfolk when she first heard the news helps me with the enormity of the task of collecting my thoughts.

But how did this all take place; the silence, the Cenotaph, the Unknown Warrior or even Poppy Day? The history of Remembrance is a schizophrenic story, its symbols of peace have their origins steeped in the mist of the Great War; remembrance didn’t just occur, it was fought for, argued over and its general shape hammered out in the years even before the carnage of the Somme in 1916. Before the rituals of remembrance could be enacted, the Army was required to completely overhaul its administration of the dead.

The fervour of recruitment during the end of 1914 was making way for the grim reality of 1915. The British Army had already been virtually destroyed and the rest of the war was to depend on the civilians from Kitchener’s recruitment drive. These weren’t the grizzled warriors who had toured the continents, but the workers from farm and factory, whose parents had carved out what they hoped would be a different future. And when their boys were killed, the family did not want their bodies discarded, they wanted them home again. A small industry began to emerge, investigating the missing and searching for the bodies of dead sons, digging them up in the most perilous of circumstance and bringing them back home to loved ones. The experience of the famous Gladstone family however, would have a long term impact upon the repatriation of the rest of the dead. The 29 year old Lt William Gladstone was killed on the 13th April 1915; he was not just another statistic of war, but the grandson of one of 19th century’s most revered Prime Ministers. The bodies of some two dozen officers had already been sent back to England prior to Gladstone and it was money and patronage that had ensured their safe return. Lt Gladstone’s body was also returned and with a certain amount of pomp and circumstance. During the whole of the war however, not one body was returned who had been from the rank and file; as a result there arose disquiet mutterings of abuse of power and wealth. If Britain was to win this war it would be up to the rank and file to deliver it and the Government were fully aware of the need to keep the people ‘onside’. There were many practical problems with repatriation, exhuming the bodies was a dangerous activity, soldiers could be killed. Other questions started to emerge, if everyone had the right to have the body returned just who would receive it, the mother or the wife? Ownership of the body lay with the Army, not so once it had been returned. And what if only parts of a body were returned? It was bad enough that an officer’s blood stained uniform was returned to the family, but body parts would have been too awful. The decision was made that no bodies would be repatriated and they would be buried in the place where they fell. In past times, soldiers came from the poorest classes, from families seeking relief from the destitution of their existence, one less mouth to feed and whilst their love was no less great there was some acceptance of those never returning. Even had they objected, the poor had no voice to represent their appeals.

Bodies of the dead from the Battle of Waterloo were treated appallingly. Here is a set of teeth which were taken from the dead and rebuilt as dentures.

In the past the bodies were in fact treated appallingly. During the Battle of Waterloo, 50,000 soldiers were buried and their bodies plundered for the new young teeth which would be used for the production of dentures. Ladies of the 19th century who could afford to buy these replacements, would be complimented for their ‘Waterloo smile’. Even as late as the 1860’s these practices were still popular, with teeth supplied by the barrel load from the fields of America’s Civil War. If the removal of the teeth from the dead was not bad enough, the bones would also become useful, being ground down and used for feeding the soil. Exactly 100 years later, there was emerging a different world; the bodies were sacred, people wanted them returned, they wanted them remembered. Organisations grew in the Great War and lobbied for their return, but whilst they were never successful, the Government knew something had to be done. A great debt is owed to Fabian Ware, a soldier with experience of the South African war and a witness to the degradation of the local military cemeteries. He was to become the driving force for the emergence of the Imperial (now Commonwealth) War Graves Commission and responsible for the respectful burial of the war dead. However, before the CWGC could go to work on carrying out the wishes of the families, the Army would need to reform its treatment of the bodies and much work had to be done in just identifying who was who.

Although officers were given the respectful burial they deserved in past conflicts, not so the rank and file whose bodies were just ploughed into mass graves. At first the soldiers wore red identity discs (dog tags) which were removed on death and this started the process of taking their name from the payment register. However, once the tag had been removed, how would the body be identified ? The mass graves ensured this was not important, but changes were now required to be made. It was not until September 1916 however, that two discs were provided; the red, as before for administrative purposes and a new irregular shaped green one to stay with the body for correct identification. The Battle of the Somme, which had started before this directive, (the infamous 1st July 1916) had approximately 100,000 men missing without bodies and 50,000 bodies without names. If you tour the cemeteries on the Somme, you will find walls of names of the missing surrounding unknown graves headed only ‘Known unto God’. As the war proceeded, the soldiers themselves took some control in having their bodies identified should they be killed and it is a particularly poignant thought. Many of the bodies that lay in no-man’s land had started to decay and even the newly made cemeteries themselves were being bombed, thereby disturbing those ‘at rest’. The identity discs, being made of leather fibre would possibly rot and therefore the equally decaying body would lose its identity.

Henry Allingham’s identity bracelet. Metal bracelets and neck tags were purchased by soldiers to ensure their bodies could be identified if left for years unfound.

Many of the soldiers, knowing they too could be left to decay in no-man’s land decided to produce identity discs made of metal, which potentially gave them a better chance of retaining their own body’s identity. It is harrowing to think that these man would be worrying about their bodies after their death, believing that they too would be left un-found and forgotten. Possibly even more upsetting is that these identity bracelets were requested of and supplied by the soldier’s own parents.

The story of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) is strangely uplifting and its existence became a source of comfort to the parents and even the soldiers themselves. Haig was a great advocate of the idea, knowing that his men’s morale was of the utmost importance in view of the human carnage they were witnessing on a daily basis. As the instruments of state started to wield some control over the care of the dead, the next challenge would be how to mark their passing once hostilities had drawn to a close.

Over a million British and Commonwealth servicemen had died during the course of the war and only those buried in home soil were as a result of returning as either sick or injured. By 1919 the CWGC was now assisting in clearing the battlefields and preparing the bodies for a decent burial in the mass cemeteries we see today. Thousands of mourners and tourists were visiting the sites and local communities were planning their own ways of remembering the dead. Some were building hospitals, memorial halls and monuments, but what was the national government to do ? How could such an enormous cataclysmic event be encapsulated in a simple, single, brilliant idea? It didn’t come easily, but eventually three icons of remembrance were to emerge; the Cenotaph, the two minute silence and the Tomb of the Unknown Warrior.

Although we recognise November 11th as the date of remembrance, it was in fact an armistice, a time when fighting was halted. The end of the war was only declared after the signing on the Treaty of Versailles on the 28th June 1919 (the exact date when Archduke Ferdinand was murdered five years earlier).

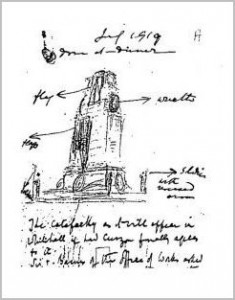

Victory celebrations in London needed to have a focal point and Lloyd George called upon Edwin Lutyens to offer some advice. He came up with an idea during lunch. There was to be a Cenotaph, a temporary structure, erected in Whitehall, London. The word Cenotaph comes from kenos, one meaning being “empty”, and taphos, “tomb”. It became an instant success; a million visitors paid their respects and laid wreaths around this empty tomb. The uncorking of such human emotion did not go un-noticed across the road in Parliament and MP’s soon called upon the structure, then made of wood and plaster, to become permanent and rebuilt in stone.

Victory Day was an enormous success, but what to do with November 11th 1919? There was now the Cenotaph to act as a focal point, but what event could take place which would symbolise the act of remembrance and have national coverage? One observer of the war noticed that when coffins of the dead passed by a crowd, a hush would descend upon it, so why not a moment of silence? A letter appeared in the Times. In spite of the protestations of King George V who thought it unworkable, a two minute silence was called for on the 11th November 1919.

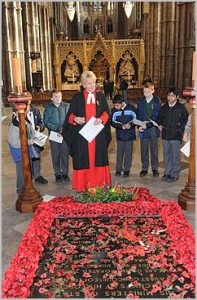

Trains, boats and vehicles would all stop and the people stilled and silenced into contemplation; the first minute for the dead and the second for the families still living. It worked to a point, but there was still something missing; there was no grave for the mourners to visit and even if one existed, it was faraway on the continent. Back in 1916, Reverend David Railton had seen a grave marked as containing an ‘Unknown Soldier’ and it gave him an idea which he retained for the rest of the war. An unknown soldier should be brought home who would represent all soldiers unknown and buried miles from home. Not until June 1920 did his idea finally connect, following a copious amount of correspondence with politicians and fellow clergymen. Four unknown British soldiers from the battles of Ypres, Somme, Aisne and Arras were exhumed and presented to Brigadier General L J Wyatt, who was blindfolded and taken to the coffins where he laid a hand upon one of them. The chosen soldier was taken through France, passing by thousands of French mourners and led by a line of one thousand school children. The carriage was the same one which brought both home both Edith Cavell and Charles Fryatt and its roof painted white for easy identification during its journey. The heavily laden symbolism continued as it was placed aboard HMS Verdun, named after the battle which was brought to an end by the British attack at the Somme. The cortège continued throughout the 7th November, attracting thousands of mourners en route to Westminster Abbey where he was laid to rest on Remembrance Day, 11thNovember 1920.

One hundred winners of the Victoria Cross, one hundred wounded nurses and one thousand mothers and wives of those fallen attended the service. His body was laid amongst the kings and queens of Great Britain, beneath a black slab of Belgian Marble and the only tomb upon which visitors to the Abbey are not allowed to stand. The impact of his arrival was immediate. He symbolised the return of the men to all mothers and wives throughout the country, many even believing that it was their own loved one placed in this tomb.

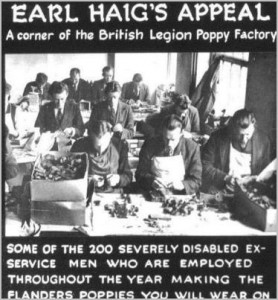

Remembrance Day was complete except for one final story, the Red Poppy. It seems shocking to us now, but on their return from war, the ex-servicemen were not treated as heroes, but shunned and seen as competition for jobs. The war had ensured that Britain’s markets had collapsed when its global customer’s sought alternative suppliers. The result was a scrabble for jobs to feed the mouths at home and the unions responded badly to the returning heroes. Many were left to wander from town to town in search of work and became resentful that women had also stolen ‘their jobs’ – it was not the land fit for heroes as had been promised and the men were angry. Historically, such rejection was not uncommon, the British sailors who fought off the Spanish Armada were held back from port and died off shore from starvation and disease. The grateful nation did not possess the funds to pay them and some of the ships’ Commanders made the payments themselves to the few who were left. British soldiers were also the subject of fear, they were hardened warriors now and the times were unsteady with revolution becoming pandemic across Europe. Money needed to be raised to support the servicemen if tragedy was to be averted and the newly formed British Legion, with Douglas (now Earl) Haig at its helm was to become instrumental in providing some of the relief required. As we now know, the seeds of Remembrance often came from experiences of the early part of war and the poppy is of that ilk.

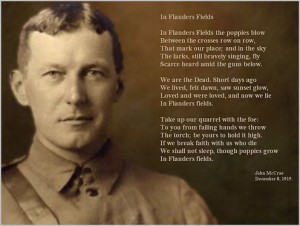

A Canadian officer, John McCrae had observed the poppies during the Second Battle of Ypres in 1915. Wild flowers often emerged from the mud, but poppy seeds in particular can lie under ground for years and will not germinate until the earth is disturbed. McCrae, sickened by death and yet inspired by the glorious colours of the poppies, then wrote ‘In Flanders Fields’. The poem was at first published anonymously, but by the time of his death in January 1918 he was famous enough to receive accolades and wreaths, one of which was made from poppies. A remarkable sequence of events then took place. The idea of poppies sold to raise money came from a Moina Michael who ensured the poppy emblem was taken up by the American Legion. A French woman, Anne Guerin observed this and used the idea to raise money to help rebuild the areas of France devastated by war. By 1920 the idea had been presented to the British Legion’s Earl Haig who quickly declared that all members should

wear a poppy on Remembrance Day. He was held in such high esteem that his words were to spread like wild fire across the nation. The Legion, unsure of its success initially ordered 1.5 million artificial poppies, but such was its popularity that shortages took places and prices were soon fetching £5 a piece. A total of 9 million poppies were eventually supplied across the country. It was a staggering response raising in 1921, £106,000 (£4 million today). In 1922, the Legion employed 41 severely disabled war veterans to produce the poppies at a rate of 1,000 pieces a day. The appeal for 1922 however, required not the 350,000 they could make but 30 million! By 1930, the Poppy Appeal was raising £600,000 (£30 million) a year, using local labour to produce them and 90% of the net income going straight to the Benevolent Fund. What makes this enterprise so outstanding was that this was achieved during one of the lowest points in our economic history.

The making of Remembrance Day is a very human story of people from all walks of life trying to find ways to help the families of then and now, come to terms with the shocking experience of war. Local memorials continued to be built throughout the 1920’s laying down the names of those who never returned and this website attempts to tell of their life’s experience from Wokingham’s perspective. War memorials are so omnipresent throughout our towns and villages it is easy for them to become anonymous, but not so with Remembrance Day. Although it is difficult to encapsulate in two minutes the enormity of remembrance, the 11th of November remains a day close to the hearts of millions.

‘IN FLANDERS FIELDS’ by JOHN McCRAE 1872-1918

In Flanders fields the poppies blow

Between the crosses, row on row,

That mark our place; and in the sky

The larks, still bravely singing, fly

Scarce heard amid the guns below.

We are the Dead. Short days ago

We lived, felt dawn, saw sunset glow,

Loved and were loved, and now we lie

In Flanders fields.

Take up our quarrel with the foe:

To you from failing hands we throw

The torch; be yours to hold it high.

If ye break faith with us who die

We shall not sleep, though poppies grow

In Flanders fields.

CLICK HERE TO READ ABOUT HOW WOKINGHAM DECIDED TO REMEMBER THEIR FALLEN