Uncle Jack Files Finnis. Died fighting for the White Russians 1919. His body returned 9 years later,

For most of us there is a settled feeling that the Great War came to a nice clean end at 11 am on the 11th November 1918. Admittedly, thousands of men were killed that morning and there are instances whereby some were killed after that time by an hour or two, but all in all, it was a fairly clean break. It was therefore with some consternation that I found a member of our family, a submariner, being killed during hostilities in the Baltic Sea in 1919. The enemy for the Royal Navy this time not the Germans, but our former allies the Russians; or the Bolsheviks to be precise. And our allies? The White Russians and the Estonians. Britain was still dreaming of control of the seas and this time the bogeymen were the Communists who were going to prevent the free trade of all ships on the Baltic. On the basis that our friends are the enemies of the enemy, we struck up with the White Russians and thereby Britain enmeshed itself in a Russian Civil War. Needless to say this was a failure, but the story has more than a few twists and turns.

The L55 was a British submarine first launched in September 1918 and played little part on the Great War, but in 1919 was sent out to engage with two Bolshevik destroyers which were laying mines to protect Petrograd. The L55 unloaded its torpedoes and missed both targets and in so doing was pressed towards an area riddled with British mines. The L55 was sunk and the Bolsheviks claimed the kill, although there is a strong possibility the loss came by way of ‘friendly fire’ i.e. via Britain’s own mines. Whichever way, it was the end of our family member Stoker First Class, Jack Files Finnis, aged 28. It was not the end of the L55 though and not the end of Jack’s story either; roll on another seven years.

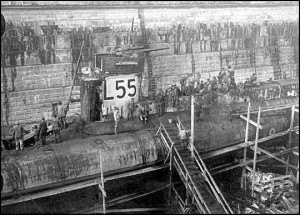

The L55 is raised from 100 feet in the Baltic Sea. The Russians are in search of submarine technology

In 1926, a trawler came across the old wreck and by 1927 Russian minesweepers confirmed the find. The now established Bolshevik government was on the hunt for new submarine technology and in 1928 announced it had successfully lifted the L55 out from a depth of over 100 feet of water. The British, aware that 42 of its souls were on board at the time of the sinking, requested the return of the bodies. This was agreed by the Russian Government, but the return would be made on to a merchant vessel as the Russians refused to have any of Britain’s destroyers in its waters. As the 34 coffins were transferred from the Truro to HMS Champion in Reval, Estonia, the local brass band played ‘Nearer my God to thee’ and the town’s flags were lowered to half mast.

The return of the bodies to England became caught up in the continuing grief of the time. The Unknown Warrior represented the servicemen from the Western Front, but now the population had 34 named sailors to grieve over. The coffins returned with great ceremony and were buried in a communal grave in the Royal Naval Cemetery Haslar in Gosport on the 7th September 1928. Two short films can be seen of the return here: Return 1 and here: Return 2. Whilst the men were laid to rest, for the L55 it was the chance to live a second life and with it, like a story straight from the mind of Stephen King, came the opportunity to kill again.

After a refit of some one million roubles, the L55 became a member of the Russian Navy and having given up many of her technical secrets, spawned a new L class of submarines for the Bolsheviks. ‘Rebranded’ the JI-55 and renamed ‘The Atheist’, the now Russian submarine entered trials in 1931. After nineteen days she sunk yet again and this time took 50 lives with her. She was still not to rest and was again recovered, this time off Kronstadt. The Athiest became a training craft until 1941 when she was again damaged, before being scrapped in 1953.

Jack’s family story twists and turns almost as much as the L55. When discovering the lost servicemen in our family tree, I always look more closely at the parents. Did they die before or after their son’s death, who were the siblings and what life did they have? Jack had a dad called Henry and an uncle Robert. The family were traditionally nautical and came from the coastal town of Deal, near Dover in Kent. After their father died and mother disappeared, they made their way around the coastal waters and into the River Thames, eventually stopping at the tides end of Teddington. In 1911 Henry had fifteen children and including Jack, he saw eleven of them die before him. Jack’s uncle Robert had five sons; four were to die in the Great War and my son is the descendent of the only survivor, an Old Contemptible who made his way through the entire war from start to finish.

My Grandfather Rupert Hammersley went down with this ship. my mother was just one year of age. My grandmother Brought her up alone with help of family. He lived in Leicester.

Hi Judith, many thanks for your contribution. I only came across this story whilst tracing my wife’s family tree and researching the Great War’s effect on a small town in Berkshire. If you have a photo and some biography details, I would be pleased to add your Grandfather to this article. My email: mrchurcher@gmail.com

Many thanks,

Mike Churcher

My paternal grandmother’s first husband was Charles Dagg. He was P.O. Telegraphist in L55 when she went down. They had been married in March 1919 and my grandmother was expecting their child at the time. As a widow she later married my grandfather who had also been widowed by the 1918 influenza epidemic. The baby was a little girl, but she died at the age of two.

Hello Frank, thanks for contributing to the story. Your family experience shows just what happened during the late stages of the war and its aftermath. Not only had the people of all countries across Europe see their boys fall in the war, but then had to cope with the flu pandemic of 1918. From memory, I think the flu killed more people than the war itself. So one war on military and another on families.

Thanks again Frank. From Mike Churcher

Those were tough times, and tough people. Time blunts the edge, but your story entails a lot of suffering. Imagine burying that little 2-year-old.. We are very pampered and soft compared those WWI people, and those between them and us, the so-called greatest generation.

Having visited the Royal Naval Cemetery Haslar, my uncle Walter H. Wash was among those who went down with her in 1919. I have the bronze medallion and award document auto-penned by King George the Vth, framed and hanging in my study in California. His sacrifice shall always be remember almost 100 years on.