Silent Highwayman. Death rows on the Thames, claiming the lives of victims who have not paid to have the river cleaned up, during the Great Stink

Flush the loo, turn on the taps and wash your hands; a simple act which came from decades of debate on the diseases and deaths which accompanied everyday life in Victorian Britain. Thanks go to Jim Bell for uncovering the local side of this disturbing story.

By 1870, Wokingham had an abnormally high death rate for a town lying outside of the traditional squalor of the industrial cities. Suspicions pointed to the possibility that there was something in the water.

In 1831 Cholera had landed in the port of Sunderland and for the rest of the century it terrorised local populations, killing them by the thousand. Concerns about disease had reached such a state that following the findings of Edwin Chadwick, the Public Health Act was introduced in 1848. The Act required local boards of health to be established in places where the population’s death rate exceeded 23 per 1,000. In Wokingham during the year of 1870, Professor J G Barford, surgeon and chemist of the local Wellington College reported Wokingham’s mortality rate at 29 per 1000, some 25% higher than the towns which were of most concern to the Public Health Act. For all Wokingham’s protestations that it was one of the most healthy places to live, there lay underneath a dirty secret which was to be exposed in 1872 by a man who was prepared to fight for a cause; an engineer by the name of John Thornhill Harrison. Before we judge Wokingham’s own sanitary failings, it is worth noting the state of Britain’s general approach to the health of its people at the time.

London 1858: The Great Stink

It was a particularly hot summer and the fetid poisons which lived within the realms of the River Thames were letting off a stench which had become unbearable to the local inhabitants. Queen Victoria had set off on a pleasure cruise, but returned within minutes due to the unbearable atmosphere and the MP’s in the nearby Houses of Parliament were left gagging into their handkerchiefs unable to cope with the stench of the river. Their solution was to propose relocating the legislative chamber to the cleaner air of St Albans! For years, the leaders in London had been aware that the filthy water had been the cause of disease; in 1849 John Snow had proved the connection between cholera and the water supply and by 1856 John Bazalgette had completed his plans for a complete overhaul of London’s ancient sanitary system. The government was shocked into action and within ten years London had built a sewage network which was to be the envy of the world; except not in East London when in 1866 another cholera outbreak claimed the lives of over 5,000 inhabitants after the local water company contaminated its own system with sewage. If the connection between dirty water and death was not realised before 1866, the enormity of these deaths drove the point home once and for all.

1866: Wokingham’s Sanitary Committee

A new law, the ‘Sewage Utilization Act’ entered the statute books in 1865 to tackle the nation’s sanitary crisis; Wokingham had suffered its own cholera attack in 1856 and endured a further two visits from the equally perilous typhoid fever. The purpose of the Act was to create a tax raising body which would provide works in areas where there was no sanitary authority. Wokingham set up a Sanitary Committee (not without great objection) to carry out these requirements. However, possibly due to the objections raised and the potential costs in building the sanitary infrastructure, it met only once and a record of the meeting was never discovered.

After five years, the central Local Government Board ran out of patience with the Wokingham Council after doing nothing to aid the town’s appalling health record. Enter the Board’s Inspector John Thornhill Harrison, a hardened engineer who had trained under the guidance of Isambard Kingdom Brunel and who came from the Sunderland, coincidentally the source of the first outbreak of Cholera back in 1831.

Charles Kingsley of Eversley. Author of the ‘Water-Babies’. He was a great advocate for the importance of clean water and it being good for the soul. Wokingham’s James Seaward was the inspiration behind Tom, the dirty chimney sweep.

It must have been like a gunslinger riding into town; this was a community in which even the appearance of a stranger would hit the newspapers, never mind a hard bitten northern engineer who was about to put the locals on trial. Harrison’s intention was to sort out this dirty old town and he was about to do some very straight talking. His report of February 1872 to the Local Government Board was very clear; Wokingham was sick and it was all down to the water, or to be more precise, the sewers. Furthermore he was angry no action had been taken in the six years since the committee first sat and stated there were no excuses. He was not alone in his fears; Professor JG Barford of Wellington College was also deeply worried by the perils of contaminated water (he later lost his position at Wellington in his zealous fight against diphtheria) and the great Christian Socialist and local author Charles Kingsley frequently gave sermons on the subject. It was no coincidence the Reverend Kingsley chose water as the subject for his 1863 book ‘The Water-Babies’. Professor Barford’s analysis of the local water showed it to be heavily contaminated with ‘solids’ and Harrison was able to point to the overflowing cesspools and open jointed piping on drains which were only designed to take away rain water. This sewage ran through the subsoil’s sandy structure and rested onto the thick London clay beneath, prompting Harrison to remark

“Can any system be conceived better calculated to pollute the water below the surface?”

Click on image to view. Before it became Tescos. Map shows sewage and water works location at Finchampstead Road in Wokingham 1890.

With the threat of central government taking direct control and the financial implications it involved, the Council lurched into action. A new committee of nine men was set up and they diligently set about listing and removing various ‘nuisances’ around the town. By 1876 the Chief Medical Officer was able to report the health of the town was showing improvement and the number of deaths had reduced from 29 per 1000 in 1870 to 16 per 1000 in the current year; below average compared to towns of similar size.

By 1878 Wokingham was credited with a much improved sanitary condition and in that year some 110 nuisances had been removed. In April 1881, Wokingham opened its new water company from a fresh water supply discovered in the Langborough area with the additional sanitary benefit that it was soft in nature and therefore highly beneficial for washing clothes. Finally, the ‘Reading Mercury’ newspaper reported on the satisfactory conclusion to the opening ceremony: ‘At two o’clock about 80 gentlemen sat down to luncheon in the Town Hall; Mr. W. Landsdowne Beale the chairman of the Wokingham Water Company Ltd presiding’.

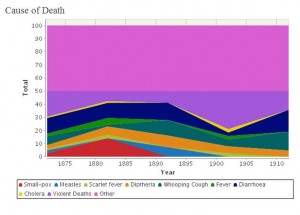

Click on image to view: The various causes of death in Wokingham during the latter half of the 19th century

Ways to die in Wokingham

The death reports in Wokingham for these years make interesting reading; the major killer through illness was diarrhoea (probably via the water system), but the largest group of identifiable deaths were those caused by violence. Victorian Wokingham it seems had more troubles than the water supply.

It is also worth noting that drinking beer at that time was understandably healthier than drinking the local water. In the time of the appalling condition of Wokingham’s water supply the number of beer houses in the area increased from about 4 in 1840 to 17 by 1869. Although the increase was in some part due to the reduction of levies in the supply of beer and cider provided in the ‘Dukes Beerhouse Act of 1830’ (that man Wellington again) it is also possible the local populace may have turned to an increased consumption in beer in order to live longer!