The War Memorial in Wokingham’s Town Hall provides 217 names of men who fell during the Great War. It is natural to assume the names are made up of all the Fallen who came from around the Wokingham town area. The real story though is not so straight forward.

It’s a question of perspective. Place yourself in that time and during the war you needed to move from one town to another. Now think about how you want to remember your loved – do you place their name in your old home (where you cannot see it) or your new town? You pay towards the new memorial and therefore you want to see it where you are living. Therefore the men named on memorials are provided by those people who wanted them remembered, they are not necessarily a list of the local men who died. Names therefore placed on the memorial may be of servicemen who never set foot in the town.

There were also those men who were local, but do not appear on the memorial. If there was no one alive or in residence to remember their death, then they might not appear on a memorial. Conversely, if there was more than one person who remembered the same person and lived in a different part of the country, then that serviceman’s name would appear on more than one memorial. They were also post war lists, fraught with the possibility of mis-spellings and nicknames as people tried to remember the names of those who died without relatives. In this respect, Wokingham’s war memorial is no different from any other. Governments did not set up the memorials, not in the way of the Imperial (now Commonwealth) War Graves Commission; they were the outpourings of people who had suffered the death of their loved one, but not received the return of the body to mourn their loss.

Although memorials are a normal part of today’s landscape, (100,000 of them in the UK) they exist almost mostly from the First World War. So how did they come about? The answer starts from a decision made by the government at a very early point in the war.

History of the 20th century war memorials

The Great War was ground breaking in the sense that it included the whole population and not just a relatively small group of professional servicemen. To coin a phrase, it was a ‘People’s War’ and the numbers were vast, with over 6 million men on active duty from Britain alone. This meant an overwhelmingly high number of deaths and the government of the time quickly took the decision to bury the men where they fell and not bring them home. The consequence of this decision was that the families of the dead were unable to mourn their losses in traditions which had been followed for centuries. Naval families had suffered this type of loss for many years and were naturally prepared for the men to be buried at sea, but the Great War was significant because its losses came from families who had no experience of military and naval deaths. The families descended into shock; the youngest son could be a delivery boy one day, a soldier the next, dead within months and no presence of a body for the family to mourn the loss. The British government was not insensitive to this loss (they also needed to keep up morale) and the response was to create the magnificent Commonwealth War Graves we see spread around the world today. Immaculate though they were, war graves on foreign soil did not provide families with the physical presence needed help mourn their loved ones.

Memorials prior to the Great War were monuments of victory not symbols of loss. This one marks the victory at Waterloo (click for source and info).

The possibility emerged that memorials could help in part to bridge the sense of loss, but these monuments traditionally represented victory and honourable battle. Following the end of the war, artists and stonemasons changed the face of memorials to reflect not the glory of victory, but the sense of mourning which had pervaded everyday life in post war Britain. Even today, memorials play an important role in mourning loss, remembrance and even hope for the future. For more information on the Story of Remembrance Day, we have posted an earlier story, which provides more detail.

How were the names collected?

Such is the enormity of the numbers of memorials across the country; it is often believed that some institution or government department was instrumental in their organisation and development. This in part was true (as in the Wokingham experience), but was also often a result of local people organising themselves to collect names and funds to build their own local memories of their fallen. Collection was often chaotic and not without objections. Wokingham took nearly six years after the war to finally unveil the Town Hall Memorial in 1924. Some councils feared that these organised groups would turn violent and become centres of revolution (Germany and Russia had already followed this route).  Luton’s Town Hall was even burned down during the festivities which followed Victory Day in 1919. Others argued about the composition of the lists, with objections to those being shot for cowardice being included. In one Lincolnshire example, a Private Charles Kirman had for nine years been a regular soldier and simply lost his nerve following years of fighting, subsequent wounds and malaria. He was executed in 1917 and as a result, was denied a listing on a proposed memorial for his home village of Fulstow in Lincolnshire. The villagers were so incensed at his omission, they refused to allow any other names to be included. Until 2005, Fulstow had no memorial to remember their dead.

Luton’s Town Hall was even burned down during the festivities which followed Victory Day in 1919. Others argued about the composition of the lists, with objections to those being shot for cowardice being included. In one Lincolnshire example, a Private Charles Kirman had for nine years been a regular soldier and simply lost his nerve following years of fighting, subsequent wounds and malaria. He was executed in 1917 and as a result, was denied a listing on a proposed memorial for his home village of Fulstow in Lincolnshire. The villagers were so incensed at his omission, they refused to allow any other names to be included. Until 2005, Fulstow had no memorial to remember their dead.

Wokingham had none of these extreme issues; their indecision was one of philosophy and therefore provides an insight into the venerable nature of our town’s leaders.

Why did Wokingham take so long to unveil its memorial?

Wokingham’s Town Hall Memorial was not unveiled until 1924, nearly six years after the end of the war. Far from avoiding the responsibility of collecting for a war memorial, the local town council led from the outset. One would have expected with such experienced leadership, agreement would have been decisive. The delay didn’t come about with the difficulty of raising the money, (which it could have been, given the post war economy was in depression) it was an argument over the best way to remember Wokingham’s fallen. The arguments which abounded over the years were unquestionably honourable and carefully considered. For a time the Comrades Club (which joined the Royal British Legion) argued the need for a place where the veterans could meet for social gatherings. Those who returned were finding it hard to relive mundane everyday life and it been recognised in the years following the end of war, that the veterans could only really find solace with other servicemen. This did not mean that the club would be to the exclusion of others; in fact they stressed their vision was as an opportunity for warm social gatherings which included children, women and people of all ages. Other arguments called for a monument, a permanent reminder of the loss and suffering experienced in the Wokingham community. Thousands of monuments had spread across the whole nation and there were calls for the Council to follow this lead. It was though, the idea of a hospital which eventually prevailed, but what type? It could be one to help repair the broken bodies of men who had returned from the war, or the elderly or children’s numerous diseases. The question which troubled the town’s elders was how to create a memorial which not only remembered the past, but could also look to the future. What had these men been fighting for, what way of life were they trying to protect and what future did they die for? Lloyd George had been unable to deliver a ‘land fit for heroes’, the post war economic depression had seen to that, but the Council were considering a memorial which made a statement, not just about the tragedy of the past, but an expression of hope for the future. The answer was just around the corner, literally.

The Council make a plan 1922

The Red Cross had recently opened a small clinic in the Town Hall, but needed larger premises to cope with the increasing demand. What if the memorial money could be used to help them find a larger home? It was the perfect symbol; if there was hope for the future, then it would come through the development and health of the community’s children. The men fought in a war selflessly and so too did the teams of nurses and doctors who worked tirelessly to repair the local children’s sick and injured bodies. The symbols went even deeper; the sick and wounded men gave themselves to the doctors, nurses and surgeons who were then able to build a bank of knowledge and skills in the following years. What better way to use those skills than on helping Wokingham’s broken children to live better lives? The men of the council were inspired and the initial decision was to support both a ‘Comrades Club’ and a children’s clinic. However by 1922, Major General Sir Walter Cayley on behalf of the Comrades Club withdrew from the scheme, leaving sole funding for a larger clinic for the children’s Red Cross.

A site had already been found, an old Methodist chapel at the bottom of Denmark Street and in July 1922, the deeds were duly presented at a ceremony in the Town Hall. Using materials donated by local tradespeople, the town’s skilled artisans volunteered to convert the chapel into a facility which would meet the demands of a modern Orthopaedic Clinic. With some pomp and undoubted pride, the Clinic was opened in April 1923 by the Marchioness of Downshire. A stone tablet was fixed to the front of the building, the inscription reflecting the sensitivities of the time:

The people of Wokingham have given

This building to be used as an Orthopaedic

Clinic in memory of the men who gave

Their lives for their country in the Great

War of 1914-1918 and in thankfulness

To Almighty God for those who came

Back in safety, confident that the memory

Of their service and sacrifice can best be

Honoured in the fight against disease and

Deformity.

Although the Orthopaedic Clinic’s work made a fine memoriam to those who fought and fell in the war, there was no single place to honour and name the individuals involved. Wokingham Town Hall also needed to think about how would remember the communities loss.

Wokingham Town Hall and its need to remember the loss.

In all the time since the war, Wokingham’s local churches had been building their own memorials to their parishioners and in particular nearly 200 men had been remembered at the local All Saints, St Paul’s and Baptist churches. Indeed the Town Hall, as a centre piece of local civil life, could not allow the community’s greatest catastrophe pass without recognition. Admiral Eustace, heading up the War Memorial Committee decided on a solid oak named plaque which would be erected in the Town Hall and placed in the ante-room alongside the Great Hall.

Collecting the names for the Town Hall Memorial.

The memorial plaque was now agreed, as had the location of its placement, but exactly whose names should appear on the inscription? It had been nearly ten years since the first man had died, so how would they be able to gather all the names with accuracy and completeness? Admiral Eustace sensibly decided to bring together the names from the local churches of All Saints, St Paul’s and the Baptist church in Milton Road which had also constructed its own memorial. That was 184 men of Wokingham in total and bringing these together would prevent another long drawn out process of a new collection of names which was fraught with the possibilities of errors because of the length of time passed.

The light beauty of the stained glass memorial inside St Sebastian’s Memorial Hall (built by the Palmer family after the war)

A researchers nightmare: 33 names without a source

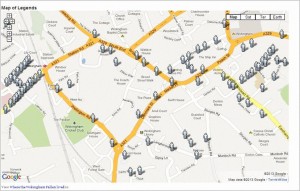

As researchers however, we discovered that the total number of names from the town’s churches would bring the total to only 184 and we know that 217 are on the town’s memorial. There were a further 33 names of which we did not know the source. Possibly it was a collection of new names which accounted for the additions. Or possibly there was another church nearby, maybe the memorials at Finchampstead or St Catherine’s church in Bearwood. On checking with both of these churches, the 33 names on the town memorial did not match. About a year after the website had been launched, we decided to have another attempt at discovering the source of the 33 men. At the start of the research, we began placing the names onto a map to show where the men had lived prior to and during the war. The main clusters were around Wokingham, but after a while we noticed that a number of them lived around Easthampstead and Crowthorne. The main church was St Sebastian’s on the Nine Mile Ride and this parish covered some of the addresses where the men lived. I had previously been to the church and knew that no memorial existed at St Sebastian’s; not all churches gathered the names for varying reasons. I decided to call back and speak to the office which looked after the grounds. It was confirmed that no memorial existed at the church, but the clerk told me they did have a list which was read out on Remembrance Day every year.

I received a photocopy and took it home. There were 33 names on the list and they matched exactly. So that was it; the names on the town hall memorial are drawn from four churches, not three. One mystery solved, but it is not completely clear why these names were used and not those of Finchampstead and St Catherine’s and possibly a number of others in the surrounding area. There is one theory though. The Palmer family (Huntley and Palmers biscuits) were a huge presence in Wokingham and they were known as generous benefactors as were others, including the Walter family in Bearwood. They had donated the funds necessary to build a Memorial Hall on the corner of Honey Hill and the Nine Mile Ride and designed a beautiful stained glass window as a central point of the commemoration. At a guess (and that is all it is) the Wokingham’s War Memorial Committee were only too pleased to combine the names of Crowthorne and Wokingham onto one memorial.

Concluding thoughts

This is as much as we know about the building of Wokingham Town Hall’s War Memorial and the story is not quite as we had expected. Some of the names are of men who never lived in the area. They are also composed from a group of people who have a link with the local churches of only one denomination. What of those who were Catholic or Jewish or even simply atheist? The men came from homes not always closely clustered around the town itself; they spread into some outer areas, but not into others. We have unsurprisingly discovered a number of local men who died in the fighting and are not named on the memorial. Although some of these observations might make uncomfortable reading, our town memorial shares these traits with thousands of other memorials from all over the nation. State departments holding databases with electoral rolls and national insurance numbers simply did not exist during this time and we are able to see just how difficult it was to collect the names of the local dead. What we see however, is a council taking leadership and a local community pulling together to build something for the future at a time when the rest of Europe of was tearing itself apart. The Orthopaedic Clinic in Denmark Street was a tremendous success and served the health of Wokingham people right up to the early 1970’s. It took a long time to deliver its own version of Remembrance, but by choosing a plaque and a clinic, Wokingham found the perfect balance between respecting its past and investing in the people of the future. Those people of the future? That’s us.

Pingback: Remembrance Day – The Incredible Story | Wokingham Remembers